Features¶

Permissions system¶

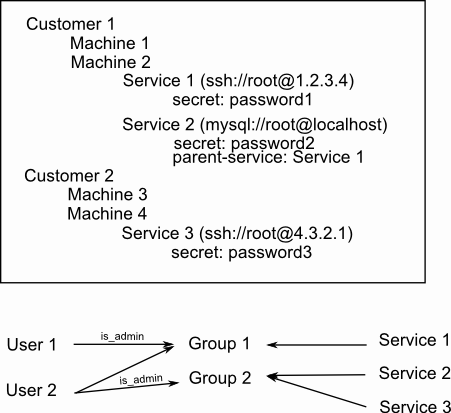

SFLvault offers a flexible User-Group-Service permission system.

Given this data representation:

User 1, being admin for Group 1, would be able to group-del-user -g 1 -u 2.

User 1, not being in Group 2, would not be able to add Service 2 to Group 1. This is a cryptographic restriction, and there’s nothing anyone can do about it. You need access to the service’s info to add it to a group. Note that a user can add a service to a group he doesn’t have access to. He only needs to currently have access to the Service by some other group.

Automatic connection¶

Tired of copying passwords to the shell ? Then typing the next ssh command, with the right parameters, then copy / pasting the next password again ?

SFLvault allows you to automatically connect to remote ssh:// servers, even in cascade, sending passwords all the way to the destination.

To do this, use the command:

$ sflvault connect [service_id]

Example:

$ sflvault connect 58

Vault passphrase: [enter your passphrase]

Authentication successful

Trying to login to server1.example.com as sshadmin ...

sshadmin@server1.example.com's password: [sending password...]

Last login: Tue Nov 18 17:36:44 2008 from yourmachine.example.com

[sshadmin@server1 ~]$ su root

Password: [sending password...]

[root@server1 sshadmin]#

To preview the steps to be done, run:

$ sflvault show [service_id]

and you’ll be shown a hierarchical view of the connections needed to reach [service_id].

Example:

$ sflvault show 58

Vault passphrase: [enter your passphrase]

Authentication successful

Results:

s#912 ssh://sshadmin@server1.example.com/

secret: password-for-sshadmin

s#913 su://root@localhost

secret: password-for-root

It creates a chain of services of any types (that must be compatible). It will provide you as a result with either a port forward or an interactive shell.

For example:

- ssh

- ssh -> ssh

- ssh -> ssh -> ssh -> mysql

- ssh -> ssh -> http(s)

ssh -> ssh¶

SFLvault will spawn a ssh process, wait for the “Password:” prompt, and send the password (received from the Vault, provided you have access to it).

It will then send an ssh command, over the previous shell, wait for the “Password:” prompt again, and send the second password.

SFLvault will drop you in an interactive shell once at the end of the chain. It handles the cases where you have shared-key authentication (when there’s no Password: prompted). It also supports the full terminal, with window resizing signals, etc.

ssh -> ssh -> ssh -> mysql¶

If we continue the ssh -> ssh example, SFLvault would simply make another hop (with another ssh command and another Password:), and then it would use the mysql plug-in to send the right mysql -u user -p command to the shell. It will wait for the MySQL prompt and then give you an interactive shell.

ssh -> ssh -> http¶

This one is a bit different, since http requires a port forward, and not a shell. So when setting up the chain, it will be configured to provide an port forward instead of a shell (which it might provide additionally).

The first ssh will be spawned locally with parameters to establish a port-forward locally to a machine on the remote site. In this first step, it will be the second ssh‘s hostname.

Then, a second ssh command will be sent through the shell, establishing another port-forward to the http service’s hostname, setting up all the intermediate port numberings to fit your needs.

Going interactive here will print the http://host:port/ for the service you’re trying to reach, something like http://localhost:12345 and will also drop you in interactve shell.

Plugins for automated connections¶

SFLvault provides a very simple interface to code plugins (like the ssh, mysql and http service handlers we’ve just seen). It’s based on Python entry_points and allows to automate tasks and add new service handlers (if you’re willing to code a quake3://server.example.com plugin :)

Plugins we currently have in the core:

- ssh (including general port forwarding)

- mysql

- sudo

- su

- postgres

- vnc

- ssh+pki

- content (some random blob content to be stored)